In Her Element

For our interview with Louise Durocher, guest editor Virginia Bunker meets up with the Seattle-based artist who sheds light on the silence of stone, the poetry in her process, and why we may need a new word for feminism.

We're intrigued by the themes that emerge and correspond with a few of our own recent observations on tactile transformation, acute authenticity, and the role of modern makers in contrast to digital lifestyles.

We hope you love this cultural conversation and exploration of ideas.

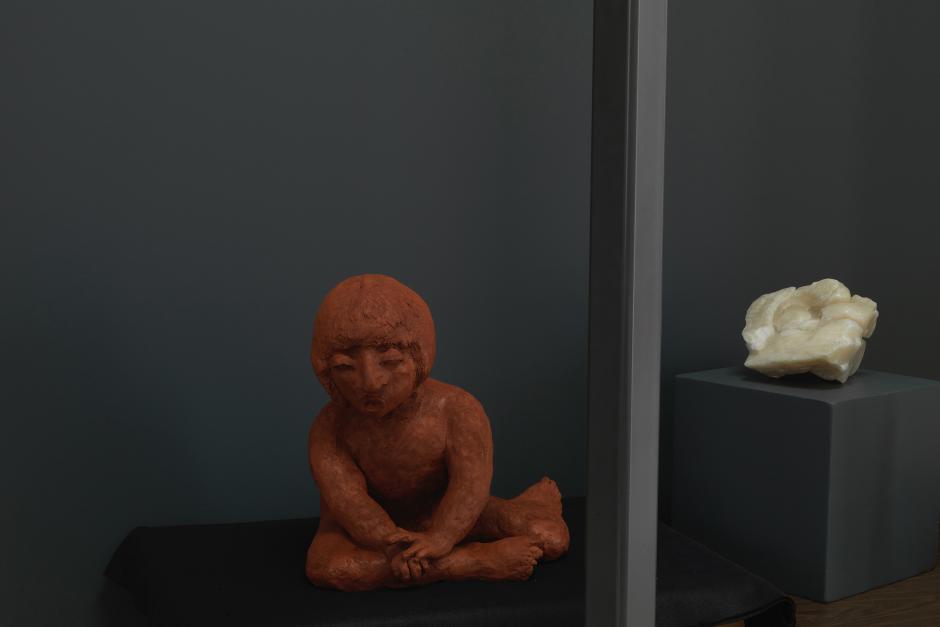

Hi Louise. It’s really great to be in your studio. But for just a moment, imagine that we’re elsewhere, meeting for the first time at a cocktail party. How would you describe your sculpture—without any photos? Hello, and sure. What am I drinking? Well, I usually say it’s contemporary figuration, but that’s confusing. My work is abstracted to a large degree, but you can always see the essence of the person or the thing it represents. All of the work comes from a human feeling or an observation of a human. That’s how it starts. I’m fascinated by the differences in people.

You’re known for many disciplines, including architecture. When did you first realize that sculpture was an ideal form of expression? As kids [in Montreal] we always had materials to paint, draw, and build with, and I was constantly building. We had a field behind our house where I’d trap butterflies and grasshoppers—and then make them little houses. My first piece in clay, at age 10, was a chess set. I’ve always been a 3-D creator more than 2-D. I live in three dimensions, inside my head as much as outside it.

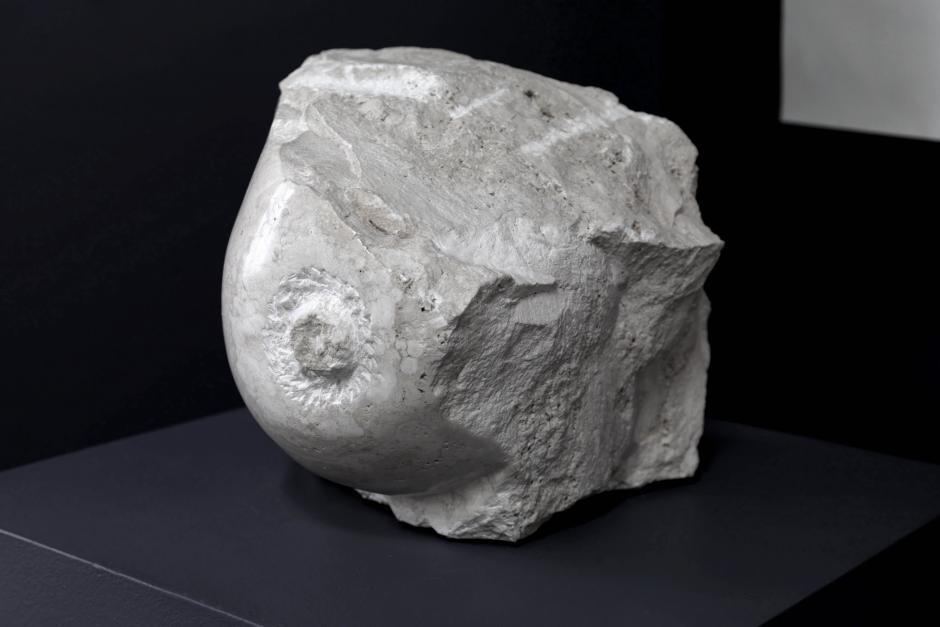

Unlike many sculptors, you do the actual physical work. Why is that important? My work is full of metaphors. Every mark I make with the chisel has a meaning—though it may not mean anything to anybody else. My textures and the lyrical part of it is really important. Eventually I will have to let somebody else do it because physically I won’t be able to continue, but I haven’t yet found an artisan who relates to my work enough that I can trust him/her. As a female [working primarily with male artisans in Italy] you’re always fighting for your place, for your piece to be what it is supposed to be.

What draws you to sculpting in stone? It’s a hard discipline. You have to think in your head, and you have to know what you are going to do. If you take a piece off, you can’t put it back on. I’m a trained ceramist—but I hate clay, though I do a ceramic piece every two or three years. But with clay you can take it off and put it on. It doesn’t make you make a decision. Working in stone there’s an intention, communication and vision—and you go and do it. I like the fact that it’s not forgiving.

Is architecture equally unforgiving? No, there are moments of pure creation. But the truth is, it’s teamwork, and clients have an enormous effect on the project sometimes. It’s like clay: you put it on, you take it off. For me, architecture is noisy. People have opinions. And in some ways, I feel like clay is noisy. Stone is silent. You have to be within yourself. It’s a solitary pursuit. You can’t be distracted.

Is there a part of the process when you’re sculpting marble that you enjoy most? The finishing. When you sand you remove something. Just by removing something you can change the light reflection. It’s your last control that will make it very pleasant to the eye. It’s truly like giving birth. 98% of the time, it’s also the moment that I can let a work go, though some pieces to this day I still cannot part from.

Where does narration come in? As you’ve said, your work isn’t figurative. I’m guessing people see all kinds of things in your sculptures? I don’t often have narratives adjacent to my work, and there’s a beauty in people seeing whatever they are going to see. I may even see it with their eyes and discover something new. But my work has a lot of emotional meaning. If someone wants to know what the essence of a piece is for me, I enjoy discussing it.

Artists seem to vary in how forthcoming they want to be. My written narrative is different than what I say in a conversation. I can’t describe my pieces in prose. I’ve tried. But poetry is best.

But poetry itself is quite coded. Exactly! And when I put a written narrative next to a piece, it’s going to be a poem. And a poem won’t clarify in the same way as if someone asks me directly. Because then I really share a more profound part of myself.

French is your first language. Do the poems come to you in French? I'm bilingual. I think and I write in French. To me the English language is more scientific writing. But some pieces only exist in French for me. Some, only in English. And some are both!

We live in such an ephemeral time, dominated by social media. Has the role of sculpture changed over the centuries? Yes. When you think of sculpture way back, it was always commissioned. People had patrons. And the pieces were mostly for private viewing and work was very representational.

So patronage meant elitist. Now access is democratic, but what about people’s ability to truly experience sculpture? It depends where you go in the world. In Kirkland [a suburban city near Seattle] there are a lot of sculptures in bronze of children and animals. Lovable and ornamental is OK. But sculpture is more than that, there’s a third leg that is more of a social comment. The kind of work that goes into the museum.

Say more on museum vs. gallery. What does that distinction mean to you? In galleries, everything that you see is to make you feel good. Beautiful. Colorful. It’s a business. People buy it to put over their sofa. You see more controversial and thought-provoking work in a museum, where it’s OK to be confronted by something unpleasant. Museums are becoming the prime place to have a social comment.

What is driving your work now? This is the first time in my adult life that I can sculpt full-time without distraction. I’m very aware that I don’t have 40 years ahead of me. I want to give it my utmost. I took architecture to an unexpected level and went to a point I didn’t expect—but sculpture is my passion. I’m curious to see if I have the guts to bring it as far as I can. It’s easy to be locked up here and do my pieces and just be content.

What else is on your mind? Well, if I had a wish, I’d wish that women artists in general would find a better place in the world. And I wish that women would help each other more. I think my next piece will reflect that.

What do you think when you hear the word “feminist?” Are you a feminist artist? The word feminist doesn’t trouble me, but I don’t feel that I wear it well. Men and women are not the same. Women are strong. Our capability is equal to men, but in a different way. 98% of my work is about women, and I’m always thinking about women, their lives, their difficulties, it’s my subject.

So is the word “feminist” too loaded? I think the word feminist had a positive power and meaning when it was used in the ‘60s and ‘70s. But in order to live in our time and move forward, we need a new word. And we have to create it. Young women today have never known what it is to be other than today. We need something to generate a positive desire…it’s the sentiment we want to convey, but we don’t have the word. And we’re dealing with a generation that’s not dealing too much with words.

Maybe it will just be a symbol? We’ll have to see.

And maybe the gender of artists will become less relevant? There was an article written a few months ago about the current wave of art collectors and how they’re tired of the men who are just coming out of art schools. Now there’s a serious interest in “old women’s’ art.” This article was written by a young woman! She says the reason galleries are now looking at old women is because in the beginning they couldn’t get recognized and at some point they said “Forget it, I might as well do the work I want to do.” So they created high-quality, grounded work that’s well executed with a history. And suddenly, whoa. People have an interest in that.

Interview has been condensed and edited.

--

Guest editor Virginia Bunker is a freelance creative, entrepreneur, and student of horticulture. Her pop-up project Future Nostalgia explores the intersection of DIY, community-based retail, and philosophy.

Insight Location

Photo Credits

Photography by Charlie Schuck for Louise Durocher.